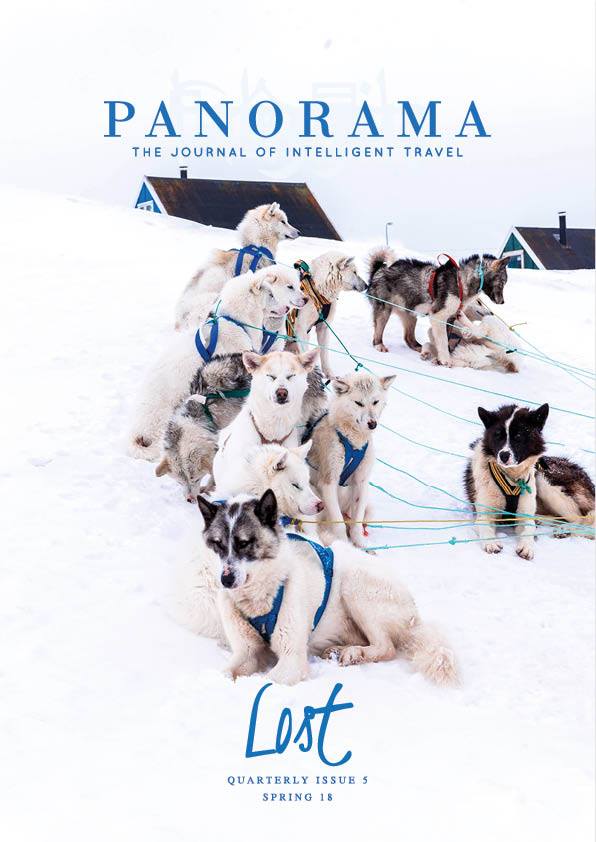

“The tail end of April found me in Greenland because of a book written by another man, old enough to be my own grandfather. An intriguing tale of the first African ever to set foot on the world’s largest island in the sixties. Years before, I’d poured through Togo-born Tété-Michel Kpomassie’s book, An African in Greenland. Fascinated by his journey, I vowed to follow some of his footsteps and see those very icebergs that had captivated him over 50 years ago. After all, I was already riveted by the Arctic, polar travel, and someday reaching the North Pole. Greenland and Svalbard had always been on my radar as well. Beyond the thrill of exploring the ends of the earth and reaching places I’d only traced my fingers across on a map, I had automatically assumed we shared the same lure of the unfamiliar. Tété had also been seduced to Greenland by a book. One he found in a Jesuit missionary bookstore about an indigenous people in a faraway land. And thus, began his plot to break from the chains of tradition to go explore this place. But as I settled into my first night in one of the most awe-inspiring places I’d ever set foot on, I wasn’t sure I wanted to continue in Teté’s exact footsteps, even though I revered them with respect. While the squall wailed and groaned outside, reminding me who was boss, I realized what drew both Teté and I to Greenland weren’t one and the same.” —Lola Akinmade Åkerström, “Going the Way of the Qivittoq”

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

“I’m a bike tourist. Three years ago, I rode across the US and Canada, over 6000 miles, 10,000 kilometres. After that trip, I looked at maps of India and wondered, could I bike tour there? My family is from Kerala, in South India, and while I’ve been back many times, I haven’t travelled much without the protective shield of aunties and uncles and cousins. I’ve never journeyed without a plan or gotten lost among a sea of brown faces. […] I know only one thing: I’ll be landing in the Himalayas, with 3500 metres of earth underneath me. The highest I’ve ever been.” —Mary Ann Thomas, From Every 100 Kilometres, A New Country: Bicycling Across India

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

“Last December in the mountains of North Carolina, sailing in the British Virgin Islands was the furthest thing from my mind. Grey settled like a wool blanket that refused to budge when day care called, and told me that Tobin threw up. On the way home, we stopped for flu basics – Gatorade, saltines – and milk for my coffee: the one thing that got me out of bed every morning.

In the dairy section, Tobin insisted on getting the milk himself and picked up a gallon of chocolate. As I redirected him toward the two percent white milk, a woman with a pixie cut called out to me.

‘Ky, right?’ Then looking down at Tobin she tapped the side of her head. ‘And don’t tell me. His name will come to me. Um…’

‘Tobin, his name is Tobin,’ I said, stalling in the hope that I would remember her name, realising I must know her from day care.

She extended her hand. ‘I’m Maya, mom to Finn, Ollie, and Callie.’

‘Three, wow,’ I said. ‘I can barely manage one.’

In the time I had been talking to Maya, Tobin added three gallons of chocolate milk beside the jug of two percent.

She laughed. ‘I have them half the time, so that helps.’

‘I’m a single mom too,’ I said.

Her face froze and I knew I said something wrong, maybe I was too enthusiastic, maybe calling someone a single mom, even by implication, was some type of slight.

‘Er, um, I’m a co-parenter, maybe that’s a better way of putting it,’ I said, trying to make amends – although I wasn’t entirely sure for what.

Her face softened. ‘I like that better. A single mom seems like you’re doing it all alone, but you’re not, are you?’

I paused, wanting to sound upbeat and still communicate the loneliness, the gaps, the hardness of it.

Before I said anything, Tobin looked up and asked, ‘Mama, you’re a single mom, mama? What’s a single mom?’

He was crawling on the underside of the cart, his belly flat on the rack meant for groceries too big to fit in side, his hands hanging between the hind wheels, his fingers prodding their diameter.

Two women walked by and one gestured toward Tobin. ‘I once saw a boy lose a finger that way, the cart ran right over it and there was blood, blood everywhere.'” —Ky Delaney, “Becoming a Pirate Mama: Rethinking Life as a Single Mom”

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

“Once, years ago, I fell madly in love with a Hungarian pianist and he fell madly in love with me. It’s wonderful when it happens like that. He came to Rotterdam for an international competition, but he performed poorly and by the end of the first day he had been eliminated from the competition. “So be it,” he said, “let’s see the Netherlands,” and I drove with this man to several cities. At an inland lake, we walked the water’s edge. But when the tide came, we were swamped, the water chest high, and had to wade to shore. Others said, “It didn’t happen. Inland lakes don’t have tides.” But it did, it did happen. This lake was once a sea. The land around it had been reclaimed, drained, and the lake hadn’t forgotten, I suppose. “Impossible,” others said. Some myths we never bother to verify. We were wet, our clothes dripping. We dried ourselves in a hotel, but nothing sexual happened. It didn’t have to. It was that exciting. We were so alive, electric. Falling in love like that was magical, even though I was married.” —Stephen Frech, “Dressed for Eden”

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

“In Bourdain’s words, from Medium Raw after his stupendously bestselling Kitchen Confidential, ‘I did not want for love or attention. My parents loved me… Nobody beat me. I got the bike I wanted for Christmas… I was miserable. I was angry.’

Bourdain was irreverent. He was our internal monologue. He articulated what we felt, in a language that was eloquent and precisely redolent in its description of the human condition.

Most American viewers and many around the globe are familiar with his rich voice, his rock-and-roll, kind of crumpled hair and T-shirt, his boots, the tired face of a man well-traveled in life and world, the face a map of deep creases and unabashed wrinkles telling us the stories he’d traveled. We are familiar with his dark eyes that fix on his friend or stranger across the table, a plate or two of food between them. We know he listened carefully to the people across the table, asking simple questions with a respect that we all deserve. He brought a familiarity to how he reached across cultures with his travel shows. But his writing is what defined what we thought of Tony Bourdain. His cigarette, unapologetic, his not-quite-regretful face after a meal liberally punctuated by alcohol, his acknowledgement of a misplaced bravado after an evening of too much drinking in Mexico or Korea, his love for travel and how lucky he’d always felt to be able to combine that with his love for food.” —Madhushree Ghosh, “The Essence of Bourdain”

Have you read Panorama yet?